As families begin to arrange travel plans again and friends gather mask-free at restaurants, the pains of the pandemic felt by the hospitality industry are still very evident.

According to the American Hotel and Lodging Association, more than 4.6 million hospitality jobs were lost in 2020, along with billions of dollars in revenue.

For UW-Stout hotel, restaurant and tourism management alum, chef and restaurateur Cindy Pawlcyn and hoteliers Rik Blyth and Scott Stuckey, this is all too familiar. But their passion for people and good hospitality drives them on.

Rebuilding from scratch

With the joy of serving people good food in a memorable setting, Cindy Pawlcyn’s sense of hospitality is at the heart of all she does.

“I love making people happy, and cooking is my way of being able to do that,” she said. “The culture, the art of it. I like that conviviality you get around the table with family and friends."

Pawlcyn graduated in 1977. She later studied cooking in Paris at Le Cordon Bleu and La Varenne. And although she was told she was too small to be a chef, she opened her first restaurant, Mustards Grill in the Napa Valley, in 1983 when she was just 28 years old.

“Anytime someone would tell me something I couldn’t do, I’d do it,” she said.

So, when the pandemic struck in March 2020 and business at Mustards dropped more than 90%, the James Beard Award-winning chef never thought of giving in. Mustards survived on carryout business and the staff of 70 was cut to four.

Then in September, the Glass Incident Fire, which destroyed much of Napa and Sonoma counties, burned down Pawlcyn’s home. She and her husband, John Watanabe, fled in the middle of the night.

“I’ve never been so scared. It pretty much charcoaled everything,” she said. “But you might as well get up and get going.”

They’re rebuilding their home, and Mustards reopened this spring with new menu options Pawlcyn spearheaded, a new outdoor seating area and a staff that’s back up to 65.

“All these phases, ups and downs … it’s been a good life,” she said. “Stout gave me the confidence I could go do it, do whatever my dream was.”

A workplace is family

Rik Blyth was bartending at a small resort while taking preveterinary classes in Madison. But he knew he wouldn’t be accepted into vet school after failing his chemistry courses.

“The bar manager was a graduate of UW-Stout and told me I was a natural for the hotel and restaurant business,” Blyth said. “I transferred to Stout a few weeks later.”

Blyth graduated in 1980. He and his wife, alum Shelley Anderson, raised their sons in the Caribbean, where he managed hotels for 25 years. He’s run resorts in Jamaica, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands and the British Virgin Islands.

While four of his hotels were destroyed by hurricanes, “no challenge compared to the pandemic. The previous disasters were financially impactful, but the pandemic was about people's health,” he said.

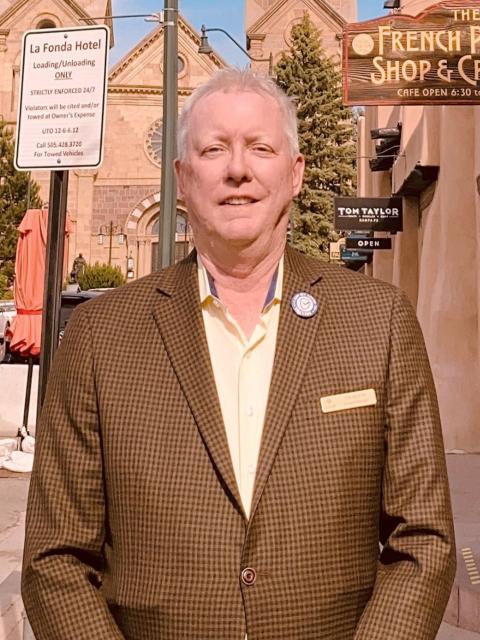

Blyth is vice president and general manager of La Fonda on the Plaza in Santa Fe, N.M., one of the few hotels in Santa Fe that never closed its doors.

Although the pandemic dramatically changed the way La Fonda operated, Blyth never forgot the human element. The hotel kept the employee cafeteria open for working and nonworking employees, paid for health insurance and assisted with unemployment claims.

Blyth’s weekly email became a lifeline. “It allowed us to reassure everyone that La Fonda had survived for almost 100 years and was not planning to close or eliminate their jobs.

“I could never imagine myself doing anything differently,” he said. “It seems trite to talk about your workplace as ‘family,’ but in 2020, that phrase was never more true.”

Moving on to the Music City

Scott Stuckey is a people person. He wanted a career in hospitality in high school when he worked at McDonald’s.

“I started college at Winona State in prelaw, but in the back of my head I knew I wanted to be in hospitality,” he said. “I visited Stout to see a friend and knew that was where I belonged.”

Stuckey graduated in 1988. In 2005, he joined Omni Hotels and Resorts and managed properties in Florida, Georgia and Pennsylvania. He started at Omni Louisville in May 2017 and saw through its construction and grand opening. He also saw it through the pandemic when it closed for more than five months in 2020.

“Having to furlough and eventually terminate more than 400 employees was heartbreaking,” Stuckey said.

This past February, after more than 30 years in hospitality, Stuckey became general manager of Omni Nashville, which has a leading reputation in the market, he said.

“I look forward to surrounding myself with great people as we build the hotel and business levels back to where they were in 2019.”

Stuckey, who serves on the HRTM advisory board, believes the opportunities in hospitality are endless, despite challenges like the pandemic.

###